The fingerstyle folk guitar of Bob Dylan (Part 2)

Folk process, song structure, strong versus ambiguous chords

Last week, we looked at how to play the fingerstyle pattern on Bob Dylan’s song “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” using Travis picking. In this week’s post, I will dig a little bit deeper into songwriting and music theory.

Imitation, theft and the folk process

One of the things I love about music is how ideas proliferate. Composers and songwriters are all influenced by the music they hear, and they incorporate these influences into their own writing. Often it’s unconscious imitation, like the rise of the flat-seventh chord alluded to in an earlier post. Musical ideas fall in and out of style based on evolving cultural preferences, and from the 1950’s through to the 70’s, the flat-seventh chord probably just started sounding good.

Sometimes, however, ideas spread through conscious acts of creative theft, as is the case of a song that uses an existing melody or chord progression. This is what I like to call a contrafact, a term originally used in classical music to refer to music created based on prior work. Aside from giving this newsletter its name, it is nowadays used in jazz music to refer to compositions consisting of a new melody overlaid on a familiar harmonic structure (i.e. borrowed chord progressions).

“Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” is a fantastic example of a contrafact. Take a listen to this recording by folk singer Paul Clayton of his song “Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons When I'm Gone?” recorded in 1960, two years before Dylan wrote his song.

Sounds familiar, right? Not only is the melody and harmonic structure similar, but the song shares the same theme and lyrics! In fact, Clayton himself took his melody from another traditional folk song “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone”, and taught Dylan how to play it. “Don’t Think Twice”, therefore, is a contrafact of “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons”, which in turn is a contrafact of the folk song “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens”.

This process of creating something from existing material is what folk singer Pete Seeger called the “folk process”, the phenomenon in which folk stories, music and art are orally passed from one generation to another. Seeger’s famous protest anthem “We Shall Overcome” derives its harmony and melody from the folk song "No More Auction Block For Me", while its theme and lyrical structure are drawn from the gospel hymn "I'll Overcome Some Day" by Charles Albert Tindley.

Contrafacts are thus what I consider the musical artefacts of the folk process. Each contrafact, through imitation and theft, preserves the musical ideas of its tradition, but at the same time helps the tradition evolve by incorporating the voice of each composer along the way, such as Dylan’s Travis picking in “Don’t Think Twice”.

Song structure and harmony

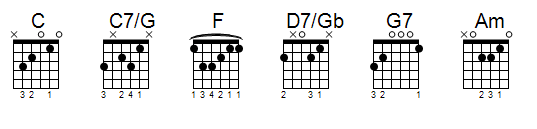

Travis picking is only one aspect in which Dylan brings in his own creative voice to the folk process. I personally find Dylan’s song a lot better than Clayton’s. But how exactly do they differ? Let’s find out. Here is a comparison between the first verse of both songs. I’ve transposed “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons” to the key of C so that it’s easier to follow.

Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons

Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right

There are two main differences that I would like to highlight - the first is how the songs are structured, and second is how they use dominant chords for transitions.

Macro and microstructure

If you listen to Clayton’s song, you’ll probably feel that it sounds a little bit more repetitive and less varied than Dylan’s. The reason for that is because it uses a much more homogenous structure. The chord progression you see here in the first verse is essentially the only chord progression of the song, which repeats several times until the end. In music theory, this is what is called a Strophic form, where you have an A section that repeats itself such as AAA.

While Dylan’s song also uses a Strophic form in its macrostructure, it has a much more complex microstructure. In fact, the passage from Dylan’s song that we’re comparing here is only half of the verse. If you listen to the last chord of the phrase “It’ll never do somehow” (G7) you’ll probably feel that it sounds unresolved - the phrase ends on a V chord (also known as a half cadence). The verse thus continues on with the following section:

If we also include the harmonica section that follows the verse, the microstructure actually consists of the following:

a - “Well it ain’t no use…”

b - “When your rooster crows..”

c - (harmonica)

And the resulting macrostructure resembles the following:

A(abc) A(abc) A(abc)

This is a lot more complex and varied than Clayton’s song which looks more like A(a) A(a) A(a), and might explain why I like Dylan’s song a lot more.

Strong verse ambiguous chords

Another perhaps more subtle difference is the choice of chords within the little “a” section. You’ve probably noticed that, in both songs, the first line ends in Am, which gives that line it’s melancholic feeling. However, Clayton’s song precedes it with a E7 chord (III) while Dylan’s with a G7 chord (V).

I personally find the first line from Dylan’s song to sound a little more melancholic than Clayton’s, and perhaps the reason for that is the relative ambiguity of the chord movement. In Clayton’s chord progression, the E7 chord creates a strong feeling of movement towards the Am chord because it is a secondary chord which serves as the dominant to the Am. Arriving at Am feels like a resolution. The G7 chord in Dylan’s progression, on the other hand, feels like it can move to multiple places - to C, F, Am, Dm.

For me, this ambiguity makes landing on the Am feel somehow more accidental, more forlorn - more sad. There’s a similar effect on the following line “If you don’t know by now”. While Clayton again uses a secondary dominant (D7, which is the dominant chord of G) to resolve to G, Dylan uses the more ambiguous F (IV) chord which sounds like the progression can go anywhere. The softer, more ambiguous chords not only make the song sound (to me) more sad, but also serve to heighten the contrast with “strong” secondary dominant chords when they do arise.

Where Dylan throws in a strong sense of direction is in the b section, where he uses the C7 (“at the break of dawn”) which pulls your ears towards resolution by the F chord (“Look at your window”). This makes a lot of sense thematically as well - the b section is where Dylan makes a strong statement of resolve.

As I hope to explore in later posts, harmonic devices such as secondary dominant chords are really powerful when creating a sense of direction by creating tension that needs to be resolved. But as I think this song shows, sometimes ambiguity can have greater emotional effect than a strong sense of direction.

Stay tuned

Thanks for tuning in! I’ll be wrapping up this short series in the next post, so make sure to subscribe if you haven’t already done so.

Let me know what you think. Is this interesting? What would you like to learn about?

And if you found this useful, share it your friends!

Until next week.

This is fantastic! Your explanations are clear and insightful.